At Lechu Neranena partnership minyan in Lower Merion, the mechitza, the partition used to divide the men and women in a prayer space, remains a fixture in the Orthodox community.

However, instead of the davening stand skewing toward the men’s side, it sits directly in the middle of the divider, equally visible to both sides of the community.

The set-up of Lechu Neranena’s prayer space — which has various changing locations in minyan member’s homes — is representative of the partnership minyan’s “liberal Orthodox” philosophy of “creating a spiritual and inclusive atmosphere within the framework of halacha,” according to the spiritual community’s website.

Founded in May 2012, Lechu Neranena is now home to 20-50 minyan members for weekly Shabbat services and holiday gatherings, though its email listserv has swelled to 227 interested parties.

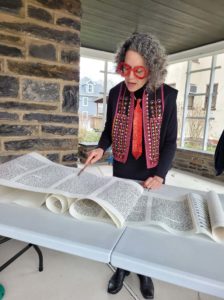

Men and women participate in their respective Torah services, with women also reading from the scrolls. Women also read the megillah over Purim and lead Kabbalat Shabbat services on Friday night.

“One of our values is to convey a sense of respect and acknowledging the importance of everyone in our community,” said Lechu Neranena board member Noah Gradofsky, a member of the partnership minyan for nine years. “It is important for everyone in the community to be able to be a part of our religious ritual in partnership.”

Partnership is the key word, Gradofsky said. Lechu Neranena is part of the partnership minyan movement championed by the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance, a national organization that uses halachic interpretations to advocate for women’s rights.

“Driven by multigenerational communal interest and leadership, partnership minyanim create an environment that is not just about giving women the opportunity to lead, but a space where men and women can lead together,” said JOFA Executive Director Daphne Lazar Price.

The concept was first developed in 2001 by Modern Orthodox Rabbi Mendel Shapiro and Bar-Ilan University Talmud Professor Rabbi Daniel Sperber, who argued that Jewish law permitted women to read from the Torah and participate in prayer rituals, under certain parameters.

In some other Jewish communities, women are not permitted to pray in front of men because it violates kol isha, the idea that men should not hear women’s singing voices, Lazar Price said. Others argue that the participation of women in the Torah services is against kavod hatzibur, the dignity of a congregation.

According to Lazar Price, Shapiro and Sperber posited that the principle of kavod habriyot, human dignity, superseded these other Jewish principles.

Partnership minyanim, including Lechu Neranena, still set some boundaries on participation. In addition to the mechitza, women do not usually lead the Saturday morning Shabbat service or maariv, evening services. Women are not permitted to lead the amidah, kaddish or kedushah.

There is some wiggle room, however. With more than 40 partnership minyanim across the world, there’s bound to be some differences in how services are led, Lazar Price said.

Courtesy of Lechu Neranena

“Some minyanim may have a spiritual leader who advises them, and who guides or leads their partnership minyan on a regular basis. Others may follow the generally accepted practices … and consult a halakhic authority as needed for particular cases,” she said.

Lechu Neranena works with halachic adviser Rabbi Martin Lockshin, who offers his services remotely. Otherwise, the community is lay-led, though some members, such as Gradofsky, are rabbis.

The members of the minyanim come from a variety of backgrounds, but share the desire for women to participate more fully in the spiritual community.

“I have a background of strong involvement with Jewish rituals and prayer groups,” said member Louie Asher, who’s been involved at Lechu Neranena since shortly after its founding. “I’ve been part of many different types, including Conservative synagogues, Orthodox synagogues, chavurot, summer camps; and I grew up in a congregation where the rabbi was a great advocate for girls and boys learning how to lead services and do various rituals.”

The Orthodox population in Philadelphia and beyond is diverse, Asher said. She maintains the importance of mutual respect: Just as she hopes other Orthodox communities respect Lechu Neranena’s decision to include women in Torah readings and services, she, too, understands why some Orthodox communities keep other rituals.

“I know that some people feel like, ‘We want to do it this way. We want our way to prevail. We want our way to be accepted here and there,’” she said. “I just accept that some people do it one way, some people do it another way; some people accept it, some people won’t accept it. I just understand that’s the way Jews are.”